Given the controversial content of this post, I’d like to remind readers upfront that this post, like all of the contents of this blog, represents my personal opinions, and in particular does not represent the opinions of my present or former employers. I am not a lawyer, nor do I claim to have read any of the patents to which I directly or indirectly allude in this posts. None of the below should construed as legal advice. Finally, the material is US-centric — your national software patent policy may vary.

My feelings about software patents are a matter of public record (e.g., this open letter to the USPTO). As things stand today, software patents act as an innovation tax rather than as a catalyst for innovation. It may be possible to resolve the problems of software patents through aggressive reform, but it would be better to abolish software patents than to maintain the status quo.

My personal feelings notwithstanding, I acknowledge the reality that today’s software companies need to have defensive patent strategies. In a previous job, one of my key accomplishments was to hire a director of intellectual property. It was a difficult hire, but it happened just in time to defend against a particularly noxious patent troll. I am not at liberty to spell out the details, but I can say that we responded with a long, expensive fight that effectively quashed the patent and the lawsuit.

Beware Of Trolls

Patent trolls, known less pejoratively as non-practicing entities (NPE) because they do not actually sell products or services that implement the systems or methods in the patents they own, take advantage of asymmetric risk. On one hand, an NPE does not need much money to bankroll (or at least initiate) a patent infringement suit — in fact, there are law firms who will take such cases on contingency. On the other hand, the company being sued faces potentially ruinous costs. Moreover, even if a company feels certain that a lawsuit against it is baseless, the company cannot count on the imperfect and inefficient legal system to reach a fair outcome. As a result, the company has to choose between spending heavily in its own defense or settling with the NPE. Most companies opt for the less risky route and negotiate settlements, providing funds that the NPEs use to sue more companies.

Some people have a name for this style of asymmetric warfare — namely, terrorism. I suppose that the word terrorist is loaded enough without increasing its breadth to include patent trolls — not to mention that trolls have their defenders. But the metaphor is a useful one. A terrorist attack inflicts an amount of damage that is much greater than the absolute cost to the terrorist, e.g., a suicide bomber who inflicts mass murder. Moreover, the threat of terrorism puts the object of that threat in the position between settling (aka negotiating with terrorists) or spending heavily on counter-terrorism efforts. As Peter Neumann notes in a Foreign Affairs article:

The argument against negotiating with terrorists is simple: Democracies must never give in to violence, and terrorists must never be rewarded for using it. Negotiations give legitimacy to terrorists and their methods…

Yet in practice, democratic governments often negotiate with terrorists.

There have been various attempts to address the threat of patent trolls.

Google litigation director Catherine Lacavera has gone on record saying that Google intends to fight rather than settle patent infringement lawsuits in order to deter patent trolls. We’ll see if Google can sustain this “we don’t negotiate with terrorists” approach; I admire the resolve, but like Neumann I’m skeptical.

Article One Partners has built a business around crowd-sourcing patent invalidation. Clients pay for research to invalidate patents, and Article One offers bounties to anyone who contributes valuable evidence. In theory, companies can request validity analysis of their own patents to test them for robustness, but I assume that the primary application of this service is the invalidation patents that a company sees as threats.

Rational Patent (RPX) has created a defensive patent pool. purchasing a large portfolio of patents and then licensing them to its member companies. Some have questioned whether this approach is “patent extortion by another name“, and indeed paying RPX for a blanket license does feel a bit like preemptively settling in bulk. But I’d be more concerned that the “over 1,500 US and international patent assets” that RPX claims to have acquired are a drop in the bucket compared to the vast number of patents that the USPTO has granted, many of dubious merit.

Meanwhile, patent trolldom is serious business. Former Microsoft CTO Nathan Myhrvold created Intellectual Ventures to “invest both expertise and capital in the development and monetization of inventions and patent portfolios.” The company has only filed one lawsuit so far, but Mike Masnick claims that it has used over a thousand shell companies to conduct stealth lawsuits.

Unfortunately, the proliferation of lawsuits by software patent trolls suggests that the economic incentives encourage such suits. If every company could sustain a “Never give up, never surrender!” approach, patent trolls would eventually go away, but it is unlikely that companies would be willing to assume the short-term risks that such an approach entails.

Moreover, this approach only works if everyone participates, requiring that every company forgo the competitive advantage it could enjoy from being the only company among its competitors to appease the trolls. This is a classic tragedy of the commons. I’m hopeful that we’ll eventually implement sensible patent reform in the United States, but I expect it will take a long time to overcome the entrenched interests that support the status quo.

It’s Not Just The Trolls

But NPEs are not the only cause for concern. Many established companies, including some technology leaders, are not averse to using patent lawsuits as part of their business strategy. The mobile device and software space is a particularly popular arena for patent litigation, the most notable being Oracle’s lawsuit against Google claiming that Android infringes on patents related to Java. The stakes are extraordinary, dwarfing even the $612.5M that RIM paid NTP in order to avoid a complete shutdown of the BlackBerry service (ironically, at least some of the patents involved have since been rejected by the patent office after re-examination).

Patent lawsuits can also be a way for larger companies to bully smaller ones. For example, a couple of entrepreneurs at visual search startup Modista were forced to shut down their company because of a lawsuit by Like.com, a more established player in the space which was ultimately acquired by Google. Note: although I was Google at the time, I have no inside knowledge of the acquisition, nor whether there is any truth to the speculation that Google acquired the company for its patents.

Defensive Patenting

Moral considerations aside, the above stories make it clear that defensive patent strategy isn’t just about NPEs. In fact, many software companies take an approach to defensive patenting is to assemble a trove of patents that are useful for countersuits and thus serve as a deterrent. Back to military metaphors, it’s similar to countries developing nuclear weapons (a popular metaphor for patents in general) in accordance with the doctrine of mutual assured destruction.

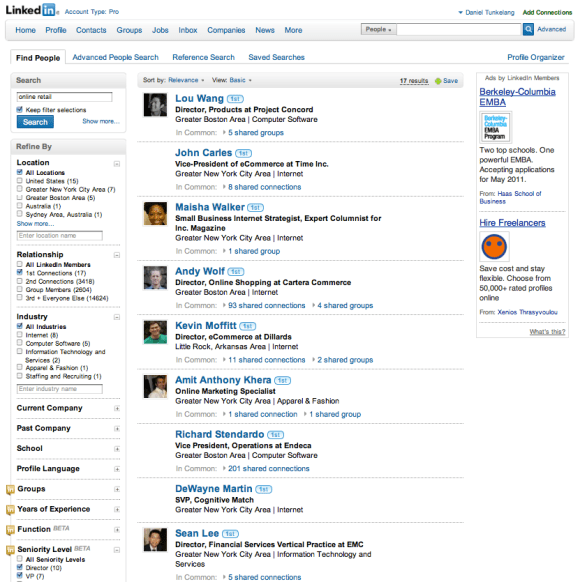

Companies that follow a defensive patent strategy typically implement a process for capturing intellectual property. Scientists and engineers file invention disclosures, a committee reviews these for patentability, and a law firm translates the invention disclosures into patent filings. The filings then go through the meat grinder of patent prosecution and eventually are extruded as patents.

It all sounds great in theory — indeed, I have seen executives who mostly worry about educating scientists and engineers about patents and providing the right incentives to encourage them to write and submit invention disclosures. Indeed, it can be difficult to integrate intellectual property capture into the process and culture of a software company. But I think there are two much bigger issues.

First, it takes several years to obtain a patent. Indeed, the USPTO dashboard shows that it takes two years just to get an initial response from the patent office. Thus a defensive patenting strategy requires significant advance planning: any patents filed today are unlikely to be useful deterrents until at least 2014. Given the rapid pace of the software industry, this delay is very significant. Moreover, startups are especially vulnerable in their first few years.

Second, intellectual property capture processes are inherently optimized for offensive (i.e., don’t copy my invention or I’ll sue you) rather than defensive (i.e., don’t sue me) patent strategy. Consider Google’s defensive position with respect to Oracle in the aforementioned lawsuit. Google has a relatively small patent portfolio, but it has obtained patents for some of its major innovations, such as MapReduce. Let’s put aside questions about the validity of the MapReduce patent — especially since patents enjoy the presumption of validity. The bigger question is to whom such a patent serves as a deterrent against patent lawsuits. It may very well deter Hadoop users, which include Google arch-rival Facebook. But, as far as I know, Oracle is not vulnerable on this front. FOSS Patents blogger Florian Mueller did an analysis and concluded that Google’s patents are not an effective deterrent. Indeed, the fact that Google has not counter-sued Oracle using its own patents is at least consistent with this analysis.

What if Google were to invest in obtaining (i.e., purchasing) a collection of broad patents that had to do with relational databases? Such patents could have nothing to do with Google’s areas of innovation and nonetheless serve as an effective deterrent against lawsuits from relational database companies like Oracle. Even if the patents were not robust, they would still have some value as deterrents because of their presumption of validity and the aforementioned inefficiency of the legal system.

In general, the most valuable defensive patents are those that you believe your competitors (or anyone else who might have an interest in suing you) are already infringing. Even if those patents would be unlikely to survive re-examination, the re-examination process is long and expensive, and even the most outrageous of patents enjoys the presumption of validity.

Everybody Into The Pool

A patent pool is a consortium of at companies that agree to cross-license each other’s patents — a sort of mutual non-aggression pact. But perhaps companies that only believe in the defensive use of patents should take a more aggressive approach to patent pooling. Following the example of NATO, they could create an alliance in which they agree to mutual defense in response to an attack by any external party. I don’t know if such an approach would be viewed as anti-competitive, but it does strike me as a cost-effective alternative to the current approach for defensive patenting.

And, as with most ideas, this one is hardly original. In 1993, Autodesk founder John Walker published “PATO: Collective Security In the Age of Software Patents“, in which he proposed:

The basic principle of NATO is that an attack on any member is considered an attack on all members. In PATO it works like this–if any member of PATO is alleged with infringement of a software patent by a non-member, then that member may counter-sue the attacker based on infringement of any patent in the PATO cross-licensing pool, regardless of what member contributed it. Once a load of companies and patents are in the pool, this will be a deterrent equivalent to a couple thousand MIRVs in silos–odds are that any potential plaintiff will be more vulnerable to 10 or 20 PATO patents than the PATO member is to one patent from the aggressor. Perhaps the suit will just be dropped and the bad guy will decide to join PATO….

Since PATO is chartered to promote the free exchange and licensing of software patents, members do not seek revenue from their software patents–only mutual security. Thus, anybody can join PATO, even individual programmers who do not have a patent to contribute to the pool–they need only pay the nominal yearly dues and adhere to the treaty–that any software patents they are granted will go in the pool and that they will not sue any other PATO member for infringement of a software patent.

It’s been almost two decades, but perhaps PATO is an idea whose time has come. And, even if a collective effort fails, individual companies might do well to focus less on intellectual property capture and more on collecting the kinds of nuisance patents currently favored by trolls. After all, the best defense is the credible threat of a good offense.

Conclusion

Even if you hate software patents, you can’t afford to ignore them if you are in the software industry. And I’m well aware that not everyone shares my view of software patents. But I hope those who do find useful advice in the above discussion. I’d love to see the software industry move beyond this innovation tax.